Ghosts of the Timberline: The Grey Wolf’s Fight for Survival in the Pacific Northwest

Once erased from the map, grey wolves have clawed their way back — reviving old fears, and old debates, across the region’s wild places.

Imagine you're sitting at a picnic table on a hot summer day beside the Columbia River, where it empties into the Pacific Ocean. The sun is relentless, and the fish guts caked on your forearms smell exactly how you'd expect. I was working for the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife back then, elbow-deep in salmon sampling, sweating through my clothes and swatting flies. And that’s when a teenager walked up to me and asked, "What do you think about wolves coming back to Oregon?"

I blinked. Not because it was a weird question—though it was—but because I genuinely had no idea what to say. Wolves? That wasn't my world. Ask me anything about salmon or rockfish, and I could give you an hour-long answer. But wolves? Totally out of my wheelhouse. The kid grilled me for 45 minutes. What was ODFW doing about wolves? Did I think they were dangerous? Did they belong here? And the truth was: I didn’t know. I hadn't thought about wolves in years.

Afterward, I couldn't stop thinking about that conversation. That teenager knew something I didn’t: the wolves were already back. And they were bringing something with them—something bigger than biology. They were bringing stories. Conflicts. Memories. So I started digging.

The Disappearance

Wolves were once everywhere. They thrived across North America, from tundra to desert, from the eastern seaboard to the coastal rainforests of the Pacific. Long before roads and fences, wolves were part of the land’s natural rhythm. But the settlers who came to Oregon didn’t see them that way.

By the mid-20th century, they were gone. Poisoned. Trapped. Shot. Oregon’s last confirmed wolf kill during the extermination campaigns happened in 1947 in the Umpqua National Forest. After that, silence.

Government bounties helped wipe them out. The livestock industry pushed hard, claiming wolves threatened their way of life. And to be fair, they weren’t wrong—wolves do prey on livestock. But the methods used to remove them were indiscriminate and brutal. Wolves were cast as villains in frontier lore, monsters lurking just beyond the timberline.

A Shift in the Wind

Then, everything changed. The Endangered Species Act passed in 1973, a landmark law that offered protection to species on the brink. The grey wolf was listed as endangered in the lower 48. For the first time in generations, the government was now trying to save wolves instead of eliminate them.

In 1995, 31 wolves were reintroduced to Yellowstone National Park. More were released into Idaho. The decision sparked outrage from ranchers and celebration from environmentalists. But almost immediately, something remarkable happened: the wolves adapted. They hunted elk. They raised pups. They stayed away from humans, mostly. They did what wolves have always done.

Dr. William Ripple, an ecologist at Oregon State University, later said, "Since the presence or absence of wolves can dramatically affect ecosystem structure and function, we believe this is a major issue for restoration, conservation and management." (OPB)

And then, slowly, the wolves began to roam.

Back to Oregon

In 1999, a lone wolf crossed into Oregon. By 2008, a pack had formed. The Imnaha Pack was Oregon’s first confirmed group in over half a century. They settled in the northeast, in Wallowa County, not far from where the last known wolf had been killed.

Each year, the population crept upward. By 2011, there were enough wolves for the state to draft a management plan. And by 2024, there were over 204 confirmed wolves in Oregon across at least 25 packs. (ODFW)

But while the wolves were returning, the debate had never left.

The Rancher's Burden

Wolves kill livestock. That’s a fact. Not always, not often, but when they do, the impact is personal. Financial. Emotional. In 2023, Oregon documented 47 confirmed incidents of wolf depredation on cattle. (ODFW) Most of these were in the same areas where wolves are most densely packed: Wallowa, Union, and Baker counties.

Compensation programs exist, but as any rancher will tell you, money doesn’t fix the stress. It doesn’t cover the time spent searching for lost calves. It doesn’t pay for sleepless nights. It doesn’t ease the anger that comes when someone from Portland tells you to be more "tolerant."

Ranchers aren’t caricatures. They’re people managing real risks in a system that often feels rigged. "They want us to coexist," one Eastern Oregon rancher told OPB, "but it feels like we’re the only ones who have to give something up." (OPB)

The Scientist's Perspective

But wolves aren’t just predators. They’re part of a broader web. In Yellowstone, their return triggered a cascade of changes: elk populations shifted, trees grew taller, streams meandered differently. Beavers returned. Birds nested in the willow groves. It was what ecologists call a "trophic cascade."

"Gray wolves are an apex species," says the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife. "They have few competitors and play a prominent role in any ecosystem they inhabit." (WDFW)

Still, the science gets politicized. Conservationists want full recovery. Hunting groups worry about competition for elk. Rural lawmakers want looser control policies. Everyone has data. Everyone has stories.

The Dividing Line

Wolves in Oregon are managed differently depending on geography. East of Highway 97, the state calls the shots. West of it, wolves remain federally protected. That line is both literal and symbolic. It separates how people see the issue.

Urban Oregonians largely support wolf conservation. A 2022 poll showed 74% favored continued protection. But in rural counties, support dropped below 50%. (Defenders of Wildlife) The wolf debate has become yet another fault line between urban and rural Oregon.

Trying to Coexist

Some people are trying to bridge the divide. Non-lethal deterrents—like fladry, range riders, and hazing—are gaining traction. A few ranchers have even partnered with conservation groups to find middle ground.

"We need to shift from conflict to cooperation," says Joseph Vaile of Defenders of Wildlife. "That means listening to ranchers, using science, and keeping the long view." (Defenders)

But coexistence is messy. It takes money. Patience. Trust. None of which come easily in places where wolves are still seen through the lens of fear.

The Fragility of Return

Wolves are back, but they’re not secure. Genetic diversity remains low. Packs are isolated. Poaching and vehicle collisions are constant threats. And the political winds can shift quickly.

A U.S. Fish and Wildlife report in 2023 warned that while wolves were rebounding in Oregon and Washington, their long-term survival wasn’t guaranteed. "All Oregon wolves descend from a small founder population from the Northern Rockies," it noted. "Their future hinges on habitat, connectivity, and consistent protection." (FWS)

Meanwhile, climate change, wildfires, and human development continue to squeeze available habitat. The margin for error is thin.

Full Circle

That teenager on the dock had no idea what he was setting in motion. His curiosity led me down a rabbit hole of history, science, policy, and perspective. And what I’ve learned is this: wolves aren’t just returning to the Pacific Northwest. They’re forcing us to confront our relationship with wildness.

Wolves are not evil. They're not saints. They’re just wolves—doing what they’ve always done. Surviving. Roaming. Raising pups in timberline dens and testing the boundaries of human tolerance.

Their presence is a reminder: this land wasn’t always shaped by us. And maybe, just maybe, we can learn to share it again.

Because sometimes, the questions that catch you off guard are the ones worth answering the most.

Stay Wild,

Micah Callahan-McNeely

Founder of Callahan Wildlife

Sources:

Government & Agency Sources

Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. (2024). Wolf program updates. https://www.dfw.state.or.us/wolves/updates.html

Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. (2024). Wolf conservation and management: Program updates. https://www.dfw.state.or.us/wolves/wolf_program_updates.asp

Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife. (n.d.). Gray wolf influence on ecosystems. https://wdfw.wa.gov/species-habitats/at-risk/species-recovery/gray-wolf/influence

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. (2023). Species Status Assessment for the gray wolf (Canis lupus) in the western United States [PDF]. https://www.fws.gov/sites/default/files/documents/20231222_western-wolf-ssa_final_508.pdf

News & Media Coverage

Oregon Public Broadcasting. (2024, July 5). Gray wolves impact ecosystems as their population increases in Oregon. https://www.opb.org/article/2024/07/05/oregon-gray-wolves-population-ecosystem-study

Oregon Public Broadcasting. (n.d.). Wolf recovery depends on your definition. https://www.opb.org/news/article/wolf-recovery-depends-on-your-definition

Environmental & Conservation Organizations

Defenders of Wildlife. (2024). Oregon releases 2024 annual wolf report. https://defenders.org/newsroom/oregon-releases-2024-annual-wolf-report

Cascadia Wildlands. (2019). Oregon Fish and Wildlife Commission votes to weaken Oregon wolf plan. https://cascwild.org/2019/oregon-fish-and-wildlife-commissions-votes-to-weaken-oregon-wolf-plan

Blue Mountains Biodiversity Project. (n.d.). Comment on the Oregon Wolf Conservation and Management Plan. https://bluemountainsbiodiversityproject.org/comment-on-the-oregon-wolf-conservation-and-management-plan

Portland Wildlife Viewing: What You’ll See This November & December

Don’t sleep on Portland’s wildlife scene just because the skies are grey. November and December bring some of the best birdwatching, urban animal movement, and quiet forest encounters of the year.

Leaves are down, trails are muddy, and casual hikers are long gone. That’s your opportunity.

Here’s what’s moving, flying, and calling this season and where to find it.

🪶 1. Waterfowl Arrivals (It’s Migration Season)

This is the best time of year to see huge flocks of geese, ducks, and swans across Portland’s wetlands.

What to look for:

Snow geese and dusky Canada geese by the thousands

Northern pintails, green-winged teal, wigeons

Early trumpeter swans (yes, already)

Where to go:

Sauvie Island (Oak Island trail and Rentenaar Road)

Smith & Bybee Wetlands

Ridgefield NWR (short drive but worth it)

🔍 Go at dawn or dusk for the best sound and sky drama. Bring binoculars. Expect mud.

🦉 2. Owl Season Begins

November kicks off owl activity in earnest — calling, courting, and hunting at dusk.

Who’s out there:

Barred owls in Forest Park and Tryon Creek

Great horned owls staking out territories

Barn owls around industrial areas and edges of town

🎧 You’ll hear them before you see them. Listen for hoots, screams, and the silence between.

🐾 3. Coyotes Are Bold Now

Urban coyotes stay active year-round, but this season they cover more ground.

Where to watch:

Johnson Creek corridor

Columbia Slough trails

Outer Eastside greenways (even along 205 paths)

They’re moving earlier in the evening and later in the morning. They’re watching you before you ever see them.

🦅 4. Raptors on Patrol

With the trees bare and prey scarcer, hawks and falcons are easier to spot and more aggressive in their hunting.

Look up for:

Red-tailed hawks perched along highways and open meadows

Northern harriers gliding low over Sauvie and Broughton

Peregrine falcons near bridges and city cliffs

Don’t forget to scan the skies. Sometimes the best action is overhead.

🐦 5. Backyard Birds Are Just Getting Started

Late fall means big changes in your yard. Keep feeders filled, especially in cold snaps.

Watch for:

Varied thrushes (finally appearing!)

Ruby-crowned kinglets in constant motion

Spotted towhees, fox sparrows, and the usual juncos

Roaming bushtit flocks that swarm feeders fast

🪟 A quiet window can be a front-row seat right now.

🧭 Want the Full Guide?

Paid subscribers get access to:

A printable November/December Field Guide - This includes photos and descriptions for identification

A Wildlife BINGO Card (perfect for trails, journaling, or kids)

📩 Sign up at callahanwildlife.substack.com to get the bonus pack.

Now’s the Time to Notice

This isn’t summer’s easy wildlife. This is subtle, quiet, wild movement. The kind of season where the more still you are, the more you see.

Take 30 minutes this week. Step outside. Bring binoculars, a notebook, or just your curiosity. There’s more happening out there than most people realize.

➡️ Subscribe and don’t miss the next guide:

👉 callahanwildlife.substack.com

The Other Oregon: Life on the Edge in the High Desert

Pronghorn - Unsplash 2025

I’m in Texas right now, in desert country. The landscape is dry, thorny, quiet. I haven’t seen much wildlife—just a few birds cutting the sky and the occasional flicker in the brush—but this place still hums with a tension I recognize.

Micah’s Substack is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

It reminds me of Oregon.

Not the Oregon most people picture or that I currently live in. Not the mossy, mist-covered forests or the dramatic coastline. I’m talking about the other Oregon—the high desert that sprawls east of the Cascades. It’s big, open, wind-scarred, and alive in ways you don’t expect. Spending time in the Texas desert this week has brought that sharply back into focus.

Oregon’s High Desert: Not Just Empty Space

Once you pass over the Cascade crest, the change is immediate. Rain-shadowed valleys give way to sagebrush flats. Ponderosa pines thin out. Mountains become dry ridges and fault-block cliffs. This is Oregon’s high desert—a region that covers nearly half the state, stretching across central and southeastern Oregon like a quiet counterweight to the coast and forest.

But this landscape isn’t just dry. It’s rich, layered, and fiercely alive—if you’re paying attention.

What Defines It?

Elevation: 3,000–6,000 feet above sea level

Climate: Semi-arid to arid, with hot summers, freezing winters

Dominant vegetation: Sagebrush, juniper, bunchgrass, rabbitbrush

Key wildlife: Pronghorn, mule deer, coyotes, golden eagles, sage grouse, horned lizards, jackrabbits

This is land shaped by fire, wind, and deep time. Volcanic activity laid the foundation. Glacial lakes receded and left behind playas, marshes, and fossil beds. The result is a place that looks still on the surface but is constantly shifting underneath.

Wildlife: Hard to See, Harder to Forget

Like in Texas, animals in the Oregon desert aren’t always out in the open. They’re crepuscular—moving at dawn and dusk. They’re camouflaged. They’re cautious. But they’re there.

You might spot:

Pronghorn—the fastest land animal in North America, gliding across open range

Greater sage-grouse—especially during spring lekking season, but sometimes visible year-round

Coyotes—silent, curious, always watching

Burrowing owls—standing at the edge of their dens in dry grasslands

Golden eagles—riding thermals above rimrock cliffs

Horned lizards and whiptail lizards sunning themselves on basalt

And we couldn’t forget the Rattlesnake —most likely curled up in the shade

And during migration windows, the wetlands and seasonal lakes in the desert—especially around Malheur National Wildlife Refuge—explode with waterfowl and shorebirds: sandhill cranes, avocets, teal, ibis, and more.

Where to Go: Towns and Gateways

If you want to see the desert side of Oregon, you need to go where the pavement thins and the distances stretch. Here are some of the best jumping-off points:

Burns / Hines

Why go: Access to Malheur National Wildlife Refuge, Steens Mountain, Alvord Desert

What you’ll see: Epic birding, pronghorn, wild horses, high ridgelines, and wide alkali flats

Bonus: Hit the Steens Loop Road (in late summer/fall when snow clears)

John Day / Fossil

Why go: Gateway to the Painted Hills and the John Day Fossil Beds

What you’ll see: Color-saturated formations, fossil history, dry hills full of mule deer and lizards

Bonus: Painted Hills at golden hour feel like standing on Mars

Painted Hills, Oregon - Unsplash 2025

Pendleton

Why go: Eastern Oregon cultural hub, with access to dry canyons and Columbia Plateau country

What you’ll see: Rolling hills, hawks, river corridors, and open ranchland

Bonus: Visit during the Pendleton Round-Up for history, culture, and real desert energy

Lakeview

Why go: Near Hart Mountain National Antelope Refuge

What you’ll see: Pronghorn herds, sagebrush steppes, natural hot springs

Bonus: Soak in Hart Mountain Hot Springs after a long day exploring

Paisley / Summer Lake

Why go: Tiny towns with huge access to desert basins and migratory bird hotspots

What you’ll see: Waterbirds, coyotes, dramatic sunsets

Bonus: Summer Lake Wildlife Area is a sunrise must

Why It Matters

Spending time in the Texas desert, even without seeing much wildlife, reminded me how easily we underestimate dry places. They don’t show off. They don’t beg for attention. But they’re full of ancient rhythms—migration, hibernation, blooming, molting, stalking, surviving.

Oregon’s deserts are no different. They’re not a lesser version of the lush side of the state. They’re an equal, opposite force—teaching patience, quiet observation, and humility. And they’re under threat from fire, invasive species, climate stress, and overuse.

And then there are the sunrises and sunsets. Wide open, horizon-to-horizon, like someone pulled the sky taut and set it on fire. They always stop me. Partly because they’re beautiful. And partly because they remind me of my husband—he used to write in letters that a good sunrise made him think of me. Said they were beautiful in the same way. So now, every time the sky flares up over a ridge or settles into that quiet lavender before dark, I pause. And I think of him.

If you care about Oregon’s wild places, the deserts matter just as much as the forests.

Texas Sunset - Micah McNeely, 2025

Callahan Wildlife Notes: Travel Tips for Oregon Desert

Go early or late in the day—especially for wildlife

Pack for extremes—hot days, cold nights, sudden storms

Binoculars are essential

Stay on trails—soil crusts and plant communities are fragile

Gas up often—services are few and far between

Respect private land—a lot of desert is fenced, but access points exist

Being in Texas has me craving a return to Oregon’s high desert. I want to see the light change on the Painted Hills. I want to hear the wingbeats of cranes at Malheur. I want to stand on the edge of the Alvord and feel like the last person on Earth.

Because the truth is: the desert is alive. It just doesn’t care if you’re watching.

Waiting to see a Tarantula,

Micah Callahan-McNeely

Founder of Callahan Wildlife

When Sea Lions Steal the Catch: The Struggle Between Oregon Fishermen and Wildlife

The Columbia River Mouth—where the river meets the Pacific near Hammond, Astoria, and Warrenton—is one of Oregon’s most vital fishing hubs. But along with Chinook and Coho Salmon runs, the region has become a hotspot for a growing conflict: fishermen vs. sea lions.

Every year, sport and charter fishermen face a familiar struggle: gear loss, stolen catches, and boat harassment—not from other humans, but from California sea lions. In fact, when I worked for Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife as a Port Sampler, it was the first issue brought up every time there was a bad experience on the water. And it’s more than a nuisance—it’s a problem with scientific weight behind it.

California Sea Lion, Unsplash (2025)

Sea Lions: Opportunistic Predators, Not Passive Observers

The California sea lion (Zalophus californianus) population has boomed from 90,000 in the 1970s to over 300,000today1. In the Columbia River estuary, these marine mammals have learned to: follow fishing boats into harbor, Steal salmon off lines or take the line until the fisherman snaps it, harass anglers and crowd fish ladders.

This behavior isn't just clever—it's disruptive.

Sea lions have few natural predators in the region. Transient orcas sometimes hunt them along the coast, but they’re rare visitors to the Columbia River. Sharks don’t enter the estuary. On land, they have no threats.

That means when sea lions push upriver, they’re effectively at the top of the food chain, which means they’re free to feed on salmon with little pushback from nature.

Chinook Salmon Under Pressure

According to NOAA, sea lions below Bonneville Dam consume up to 43% of the adult spring Chinook run2. Some individuals have been observed taking multiple salmon per day—many of which are listed under the Endangered Species Act (ESA).

Despite hatcheries, dam improvements, and fishing restrictions, predation by marine mammals is now one of the top threats to salmon survival in the Columbia Basin.

There are many people in Oregon concerned about this issue but if your livelihood isn’t on the water, it probably hasn’t crossed your path. There are entire counsels in Oregon dedicated to salmon in Oregon and the issues that salmon and fishermen face. See Oregon Salmon Commission here. And see ODFW Commission here.

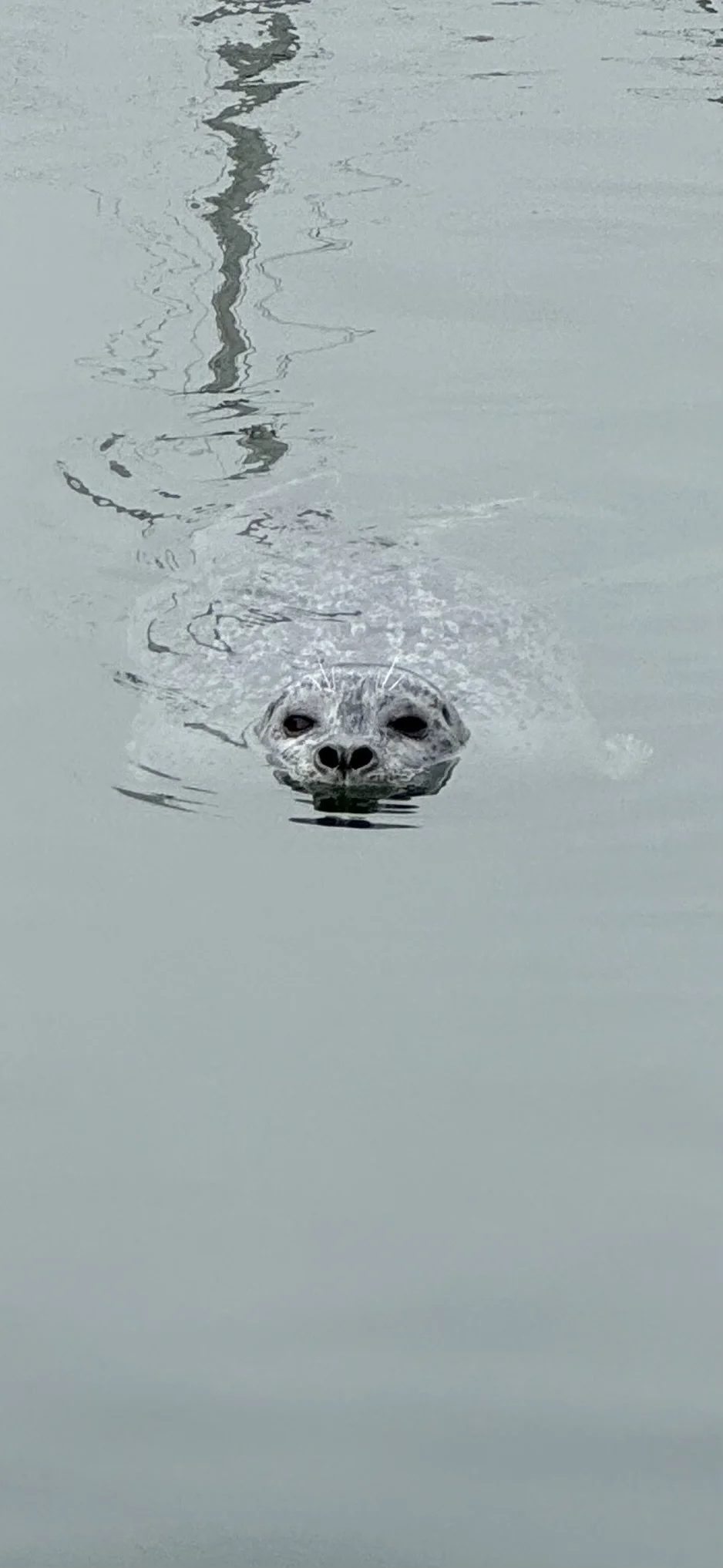

(Harbor Seals Are Not the Same Problem)

Dock crews may lump them together, but harbor seals are a different story:

They weigh less.

Stick closer to shore.

Feed mostly on small fish or scraps.

Rarely interfere with active fishing lines.

They’re a mess around cleaning stations—but they’re not chasing your catch. In fact, comparatively they are ‘friendly’. They pop their head up a few times, observe and then go away if no bait or fish carcass is being dumped.

Personal Photo of a Harbor Seal off the Astoria, OR Docks (2024)

Human Habits Are Fueling the Fire

A major issue I saw while working for the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW) was anglers dumping fish guts directly into the harbor. Usually it’s not allowed at most docks and fishermen are aware that it’s against dock rules. But it’s obvious when it’s not observed.

The result? Massive flocks of gulls. Seals and sea lions flocking to the docks. Increased aggression and habituation.

Conditioning wild animals to expect food near humans is dangerous—for both sides3.

Because sea lions are protected by the Marine Mammal Protection Act, most deterrents are off-limits. Recent federal changes allow for targeted removal of individual sea lions at critical choke points, but this doesn't help the average sport fisherman on the open water4.

Even when devices like pingers or air horns are used, sea lions quickly adapt.

What Fishermen and the Public Can Do

If you fish in the Columbia or care about salmon survival, here’s how you can help. Don’t dump fish waste in the harbor. Use proper disposal bins at the dock. Report aggressive sea lions to ODFW. Support balanced wildlife policy that includes predator management, take to the commissions and get involved. Share the science, not just the frustration.

When Man Meets Wild, Responsibility Matters

The Columbia River is a collision point between wild instincts and human activity. If we want to preserve fishing, salmon, and sea lions alike, we need smarter coexistence—backed by science, not just stories. Fishermen will tell you exactly how they want to handle the issue — and it’s not good for anyone. But ODFW will tell you that they have their hands tied — and they do. So where do we go from here? How do we handle Man v. Wild justly?

Want More Behind-the-Scenes from the Columbia River Docks?

🎣 Follow my ongoing stories, insights, and real-life reporting from the Oregon coast on Callahan Wildlife on Substack

You’ll get more deep dives into where man meets wild, straight from someone who’s been on the docks, boats, and cleanup crews.

Stay Wild,

Micah Callahan-McNeely

Founder, Callahan Wildlife

Micah Salmon Fishing in Columbia River, 2024

Sources:

NOAA Fisheries, California Sea Lion Stock Assessment Report (2021)

NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-NWFSC-137 (2017): "Evaluation of Pinniped Predation on Adult Salmonids and Other Fish in the Columbia River Basin"

Marine Mammal Science (2020): “Human-induced food conditioning in marine mammals: patterns, causes, and consequences.”

John D. Dingell Jr. Conservation, Management, and Recreation Act (2019), Section 302: Authorizing lethal removal of sea lions in certain areas of the Columbia River.

The 5 Best Places for Fall Wildlife Viewing Near Portland, Oregon

By Callahan Wildlife

Fall in the Pacific Northwest is far more than leaf-peeping season. Around Portland, it’s a window into wild migration, feeding frenzies, and shifting ecosystems. Birds flood the wetlands. Elk bugle in the mist. Salamanders skitter through soaked forest floors. If you’re looking to witness wildlife in motion—especially within 50 miles of downtown Portland—here are five of the best places to explore this fall.

1. Oaks Bottom Wildlife Refuge – Urban Wetland with a Wild Heart

Distance from Downtown: ~5 miles

Species to Watch: Great blue herons, wood ducks, green-winged teals, northern pintails, bald eagles, beavers

Oaks Bottom is proof that you don’t need to leave the city to find real wildlife. This 170-acre refuge sits right below the Sellwood neighborhood and buzzes with migratory bird activity in the fall. Waterfowl flock to the seasonal wetlands, and you’ll often spot bald eagles hunting overhead or perched in cottonwoods. Herons stalk the shallows while beavers engineer evening flood control.

Why fall is special: The seasonal drawdown of water exposes mudflats, creating prime stopover habitat for shorebirds. October is peak bird traffic—bring a scope if you have one.

2. Sauvie Island Wildlife Area – A Migratory Bird Mecca

Distance from Downtown: ~20 miles

Species to Watch: Sandhill cranes, snow geese, tundra swans, American kestrels, black-tailed deer

Come fall, Sauvie Island transforms into one of the Pacific Flyway’s busiest layovers. Tens of thousands of migratory birds funnel through the island’s managed wetlands, including the iconic sandhill cranes whose rattling calls echo across the fields. The best part? It’s all accessible—via short trails or roadside pullouts.

Pro tip: Visit the Rentenaar Road viewing area for morning light and minimal crowds. Bring binoculars and patience.

Note: Portions of the area close for hunting seasons, so check the ODFW website before you go.

3. Tualatin River National Wildlife Refuge – Accessible Wildlife with a Conservation Story

Distance from Downtown: ~15 miles

Species to Watch: Cinnamon teals, American bitterns, western pond turtles, red foxes

TRNWR is a gem for fall wildlife watching, especially with its flat, ADA-accessible trails and strong interpretive signage. The refuge is part of an ongoing effort to restore seasonal wetlands and native oak savanna—a major win for local biodiversity. It’s an especially good spot for beginner birders or families, but even seasoned biologists will find plenty to observe.

Watch for: Bitterns camouflaged in the reeds and turtles basking during warm fall afternoons. The wetlands begin to refill by mid-to-late October, drawing back a huge mix of ducks.

4. Tryon Creek State Natural Area – Amphibians and Old-Growth Atmosphere

Distance from Downtown: ~7 miles

Species to Watch: Rough-skinned newts, Pacific tree frogs, pileated woodpeckers, black-tailed deer

If wetlands are too crowded, shift gears and head into the forest. Tryon Creek, nestled between Portland and Lake Oswego, is one of the few state parks within a major metro area. Its cool, shaded ravines make it ideal for spotting amphibians in fall—especially after the first rains hit. Rough-skinned newts and salamanders begin migrating from their summer hideouts to breeding pools.

Seasonal bonus: Look up. Tryon’s mature Douglas-fir and bigleaf maple canopy is alive with woodpeckers, flickers, and nuthatches stocking up before winter.

5. Scappoose Bay and St. Helens Wetlands – Underrated Coastal Confluence

Distance from Downtown: ~30 miles

Species to Watch: River otters, belted kingfishers, coho salmon, osprey, red-legged frogs

Often overlooked for Sauvie Island, the wetlands and backwaters around Scappoose Bay offer a quieter—but no less dynamic—fall experience. The confluence of river, estuary, and wetland habitats supports everything from salmon runs to raptor hunts. Kayak-access makes this area especially unique—paddle quietly and you may be rewarded with a glimpse of a river otter family or leaping salmon.

Salmon run alert: October and November are prime months for spotting coho salmon returning to spawn. Bring polarized sunglasses to see into the water.

Final Thoughts: Why Fall Matters for Wildlife Viewing

Fall isn’t just beautiful—it’s biologically intense. As an aspiring biologist and lifelong wildlife observer, I see this season as a living lab: migration in real-time, animal behaviors shifting with the light, and ecosystems resetting for winter.

If you’re tracking wildlife trends, building your field notes, or just reconnecting with nature, these five spots are close enough to visit often—and wild enough to surprise you every time.

Want more local wildlife insights like this?

Sign up for the Callahan Wildlife newsletter (coming soon!) and follow along as I document Oregon’s ecosystems, research findings, and ways to get involved in conservation.

This is just the beginning.

Stay wild,

Micah L. Callahan

Founder, Callahan Wildlife

The Majesty of Winter: Snowy Owls in the Pacific Northwest

As the winter chill settles across the Pacific Northwest, a rare and regal visitor graces our open fields and coastal dunes—the Snowy Owl (Bubo scandiacus). With their striking white feathers and piercing yellow eyes, these Arctic wanderers captivate bird enthusiasts and nature lovers alike.

Snowy owls are a true winter wonder, traveling south from their breeding grounds in the tundra during colder months in search of food and milder conditions. Their arrival offers a unique glimpse into the lives of one of the world’s most iconic and mysterious birds.

In this feature, we’ll explore the snowy owl’s fascinating migration patterns, adaptations for winter survival, and their critical role in the ecosystems they visit. We’ll also share tips for spotting them in the Pacific Northwest and how you can contribute to conservation efforts.

Bundle up and join us as we delve into the story of this majestic bird, a symbol of winter’s beauty and resilience.

Migration patterns:

Snowy owls exhibit a range of migration patterns, often traveling from their Arctic breeding grounds to more temperate regions during the winter. These movements vary yearly, influenced by factors such as prey availability and weather conditions.

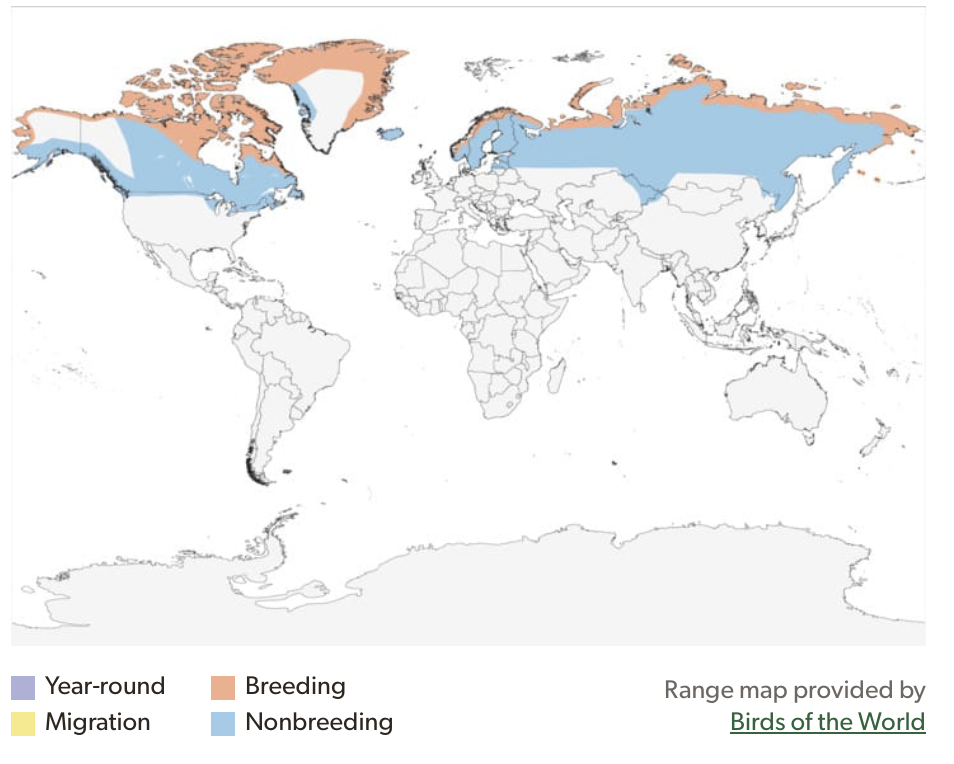

According to data from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s All About Birds, snowy owls are primarily found in northern parts of the United States, with sporadic appearances as far south as Texas during years of extreme irruptions.

Figure 1. Distribution of Snowy Owls in the World, to include breeding ranges.

Figure 2. Distribution of Snowy Owls in North America, including breeding ranges.

The primary habitat for the Snowy Owl is the Arctic Tundra, this form of habitat is extremely harsh and is defined as the following: “Tundra ecosystems are treeless regions found in the Arctic and on the tops of mountains, where the climate is cold and windy, and rainfall is scant. Tundra lands are covered with snow for much of the year, but summer brings bursts of wildflowers” (Nunez, National Geographic, 2019).

Adaptations for Winter Survival:

Because the Snowy Owl often lives in the Arctic Tundra, their adaptations are specific (like any animal) to its habitat. Adaptations are physiological changes that occur over generations to increase fitness. Fitness being the biological term for the ability to reproduce and offspring ability to survive. A big theme in biology is an animal’s ability to adapt, reproduce and increase fitness. One important thing to point out is that mutations are random and don’t necessarily increase fitness (potentially deadly even) and mutations are often adaptations that are positive.

General Owl Adaptations:

Head Rotation: Owls can rotate their heads 270 degrees, allowing them to compensate for their immobile eyes and scan their surroundings with precision.

Night Vision: Large, light-sensitive eyes enable them to hunt effectively in low light, a critical adaptation for species living in regions with extended periods of darkness.

Silent Flight: Specialized wing feathers reduce noise during flight, giving them an advantage when hunting prey.

Snowy Owl-Specific Adaptations:

Snow Camouflage: Their white plumage blends seamlessly with snowy landscapes, providing both protection and stealth in hunting.

Insulation: Dense feathers cover their entire bodies, including their legs and feet, conserving heat in freezing temperatures.

High-Calorie Diet: Snowy owls consume up to a pound of food daily to sustain their elevated metabolic rate. Their primary prey, lemmings, provides the energy needed for survival in harsh conditions.

All Adaptions are sourced to the Owl Research Institute.

Critical Role in Ecosystems:

Snowy owls are apex predators in their habitats, playing a vital role in regulating prey populations.

Rodent Control: A single snowy owl can consume up to 1,600 rodents per year (Lawlor, Oceanwide). By keeping rodent populations in check, they prevent overgrazing and maintain vegetation health, which benefits the broader ecosystem.

Keystone Species: Their predation impacts prey dynamics and influences the population sizes of other predators that rely on the same food sources.

The snowy owl’s dependence on lemmings is so significant that lemming population cycles directly affect snowy owl breeding success. This predator-prey relationship underscores the interconnectedness of Arctic ecosystems.

Lemming, primary prey for Snowy Owls

Spotting Snowy Owls:

Catching a glimpse of a snowy owl is like finding a four-leaf clover—they are elusive and often inhabit areas far from human activity. However, during colder winters, they may migrate to the Pacific Northwest, offering birdwatchers a chance to observe them in coastal and mountainous regions.

To improve your chances:

Visit open, snow-covered areas like agricultural fields, coastal dunes, or quiet mountain trails.

Use tools like the eBird database from the Cornell Lab to track sightings in your area.

Figure 3. Active sightings map of the Snowy Owl from eBird Observations via the Cornell lab 2019 - 2024, link. This is updated periodically, the above is a screenshot from time of posting this blog.

Conclusion:

The snowy owl is more than a symbol of winter’s beauty—it is a cornerstone of Arctic ecosystems and a reminder of the fragility of our planet’s biodiversity. By learning about this remarkable bird, we not only deepen our appreciation for nature but also take a step toward protecting it.

As climate change continues to alter ecosystems, the snowy owl’s survival depends on our commitment to conservation. Support organizations like the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and the Owl Research Institute, and consider participating in citizen science projects to aid ongoing research.

Together, we can ensure that future generations will also marvel at the majesty of the snowy owl.

Resources to Explore:

Cornell Lab of Ornithology: Offers species information, ID tools, and migration maps. Try their app, Merlin Bird ID, for quick identification.

Owl Research Institute: A premier resource for detailed information on owl ecology and behavior.

For more features on Pacific Northwest wildlife, visit Callahan Wildlife, where science meets community engagement!

Pollinators in the City: Protecting Oregon’s Bees, Bats, and Butterflies in Urban Environments

As of 2019, 56% of the world’s population resides in urban areas (Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2019). While cities offer hubs of innovation and development, they also face unique challenges—including food security and the growing strain on agricultural systems. With 40% of Earth’s land dedicated to agriculture (Pye-Smith et al., 2022), urbanization puts additional pressure on our ability to feed the planet. Compounding this issue is the alarming decline in pollinator populations, which are critical to our ecosystems and food supply.

To combat these challenges, urban planners are increasingly integrating green solutions like rooftop gardens, green spaces, and even urban agriculture—such as vertical farms and rooftop crop cultivation—into city designs. An emerging focus within these initiatives is creating habitats where pollinators can not only survive but thrive, ensuring the health of urban ecosystems and contributing to broader ecological resilience.

Why Pollinators Matter in Urban Environments

Pollinators—including bees, butterflies, bats, and other species—play a vital role in maintaining biodiversity and supporting agricultural production. In Oregon, known for its vineyards, rose gardens, hay fields, and strawberry crops, pollinators are essential to sustaining both local economies and cherished landscapes. Without these creatures, many plants would fail to bloom, fruit, or reproduce, disrupting the intricate food web that supports wildlife and humans alike.

However, urbanization, climate change, and habitat loss are increasingly threatening pollinators. Oregon’s cities, like Portland and Eugene, face growing pressures as they expand. By integrating pollinator-friendly practices into urban spaces, we can mitigate these challenges while enhancing the resilience of local ecosystems.

Supporting Pollinators in Oregon’s Cities

Whether you live in a bustling city, a suburban neighborhood, or a rural area, there are simple and effective ways to support pollinators. Here are three impactful strategies:

1. Plant a Diversity of Nectar and Pollen-Rich Plants

Creating pollinator-friendly spaces doesn’t require a sprawling garden—small efforts make a big difference. Consider planting native species that bloom throughout the year to provide a continuous source of food. Options like lavender, sunflowers, and Oregon grape not only attract pollinators but also enhance your space’s natural beauty. Window boxes, flower beds, pots, or even vertical gardens are all viable options, especially in urban settings with limited space.

2. Avoid Harmful Pesticides

Many pesticides, particularly neonicotinoids, have long-lasting, detrimental effects on pollinator health. These chemicals can remain active in plants and soil for years after a single application. Opt for natural pest control methods or organic products that are safe for pollinators. By reducing pesticide use, you protect bees, butterflies, and other vital species while promoting healthier ecosystems.

3. Create and Preserve Habitat

Pollinators need safe spaces to nest, forage, and rest. You can support them by leaving portions of your yard unmowed, maintaining leaf litter during the fall, or planting native shrubs and trees. For bats, consider installing a bat box—a simple structure that provides shelter and encourages these nocturnal pollinators to roost nearby. While these measures might seem small, they collectively create a network of resources that urban pollinators rely on for survival.

Urban Ecology in Action

Cities worldwide are recognizing the importance of pollinator-friendly initiatives. Portland, for instance, boasts numerous community gardens and green rooftops that provide habitats for pollinators while enhancing urban sustainability. These efforts not only support wildlife but also contribute to climate adaptation by reducing urban heat islands and improving air quality.

Globally, cities like Singapore and London have pioneered urban greening projects, proving that even densely populated areas can foster thriving ecosystems. By following these examples, Oregon’s cities can continue to grow while preserving the natural elements that make the Pacific Northwest unique.

Your Role in Protecting Pollinators

Supporting pollinators doesn’t require grand gestures—small, consistent actions can make a profound impact. By planting a few pollinator-friendly flowers, avoiding harmful chemicals, or advocating for green infrastructure in your community, you contribute to a healthier environment for both wildlife and people.

Together, we can ensure that Oregon’s bees, bats, butterflies, and other pollinators have a place to thrive, even in the heart of our cities.

Wildlife and Pest Control: How Small Businesses in the Pacific Northwest Are Tackling Invasive Species

In the beautiful Pacific Northwest, the unique landscapes and rich wildlife face a growing threat from invasive species. These are plants, animals, and insects that didn’t originate here but have taken root – often in ways that harm our natural ecosystems. For local pest control businesses, helping communities manage these invasive species has become an important part of their work, requiring a thoughtful approach to protect both local wildlife and people’s properties.

Why Are Invasive Species a Problem?

Invasive species are like uninvited guests who disrupt the party. When these plants and animals show up in an ecosystem that didn’t evolve with them, they often spread aggressively, outcompeting native species for food, space, and other resources. For example, the Himalayan blackberry – as tasty as it is – can crowd out local plants, reducing the habitat that native animals rely on. Similarly, species like nutria (a large, aquatic rodent) damage wetlands, making it harder for fish, birds, and amphibians to thrive.

These changes affect not just the plants and animals, but the entire environment, impacting the biodiversity that makes the Pacific Northwest special. This is where local pest control businesses come in, using strategies to keep invasive species in check while respecting the balance of our natural world.

The Rise of Eco-Friendly Pest Control

More and more, pest control companies are recognizing that sustainable practices are key to managing invasive species. Traditional methods relied heavily on chemicals to get the job done, but that can often harm other plants, animals, and water sources nearby. Today, a lot of pest control companies are using something called “Integrated Pest Management,” or IPM, to handle invasive species more thoughtfully.

IPM is like a toolkit of eco-friendly methods that prioritize prevention and smart, targeted actions. For instance, instead of spraying large areas with pesticides, companies might introduce natural predators that target invasive pests. Some businesses bring in insects that munch on specific invasive plants or even use fish species that eat mosquito larvae, helping to manage pests without endangering native wildlife.

Working Together With the Community

Many pest control businesses understand that they can’t do this work alone – and community collaboration has become essential. Educating the public about invasive species helps prevent their spread in the first place. Simple actions, like washing hiking boots and gear after being outdoors or avoiding the release of aquarium plants and animals into rivers, can make a huge difference.

Local businesses often join forces with parks departments, neighborhood groups, and conservation organizations to spread awareness. They might even organize “invasive plant cleanup” days, where community members are invited to help pull out problematic plants like ivy or blackberry bushes. This teamwork builds a strong sense of local stewardship, making invasive species control a shared effort.

Challenges and What’s Next

Dealing with invasive species is no small task, especially as climate change creates more favorable conditions for these invaders to spread. But the dedication of local businesses, armed with sustainable pest control techniques, is making a difference. By using eco-friendly approaches and working closely with communities, these companies are helping keep our landscapes healthy and balanced.

Supporting businesses that prioritize sustainable practices is one way we can all play a part. By choosing companies that care about protecting native species, you’re not only helping to keep your home safe from pests but also supporting the health of the Pacific Northwest’s natural habitats.

Simple Ways You Can Help

Want to get involved? Here are a few easy ways to support the fight against invasive species:

Clean your gear: Whether you’re hiking, biking, or boating, wash your equipment to prevent spreading seeds or pests.

Learn to spot invasives: Familiarize yourself with a few common invasive species in your area, so you can report sightings to local authorities.

Choose sustainable pest control: When you work with pest control services, consider companies that use eco-friendly methods.

Together, through community effort and mindful choices, we can protect the Pacific Northwest’s incredible biodiversity from the threats posed by invasive species. Let’s keep this region’s wildlife and landscapes healthy for generations to come!

Urban Predators: How Coyotes, Raccoons, and Hawks Thrive in Oregon’s Cities

Introduction

On my way to work at 3 a.m. this morning, groggy and uncaffeinated, a dog-like figure suddenly appeared in my backup camera. As I slowly backed out of my driveway in my very suburban neighborhood, I realized it wasn’t a dog—it was a coyote. Its bushy tail and the distinct shape of its head were unmistakable features that Oregonians have come to recognize as belonging to one of our most resilient predators. Thirty years ago, you were far more likely to encounter a coyote on farmland than in Southeast Portland, especially in areas without nearby natural habitats. Like many Oregonians, I found myself wondering, “Why is it here?”

As Oregon’s cities expand and natural habitats fragment, wildlife is adapting to urban life in fascinating ways. Predators like coyotes, raccoons, and hawks are not only surviving but thriving in our cities, ushering in a new chapter of human-wildlife interactions. In this post, we’ll explore why these predators are drawn to urban areas, how they’re adapting to city life, and what their presence means for residents and ecosystems alike.

Coyotes in the City

Coyotes are some of North America’s most adaptable predators, and their presence in urban areas like Portland and Eugene is steadily increasing. Their flexible diet—which includes everything from small mammals to fruit—makes city life surprisingly appealing. Known for their intelligence and agility, coyotes can navigate human environments with ease. However, their presence can also create challenges; they may occasionally prey on pets or rummage through trash, sparking concern among residents. Awareness campaigns and local wildlife policies are essential for managing these interactions peacefully and safely.

Raccoons: Clever and Capable Urban Foragers

Raccoons, with their dexterous paws and problem-solving skills, are ideally suited to urban environments. From scavenging in trash bins to finding shelter in attics, raccoons have developed a “toolkit” that allows them to thrive in cities. While they may sometimes be a nuisance to homeowners, these creatures contribute to urban ecosystems by controlling insect populations and cleaning up waste. Finding a balance between their natural behaviors and human needs requires respect and understanding on both sides.

Hawks: Nature’s Pest Control

Raptors like red-tailed hawks are a common sight in Oregon’s city parks and green spaces. These birds of prey play a valuable role in controlling rodent populations, providing a natural form of pest management in urban areas. But city life presents challenges for hawks, too; high-rise buildings and busy roads can be dangerous. Local organizations in Oregon are working to protect and support urban hawk populations through habitat preservation and public awareness campaigns.

What Does This Mean for Us?

The presence of these urban predators offers a unique opportunity to observe wildlife up close, but it also requires some adjustments on our part. Simple actions, like securing garbage, supervising pets, and respecting wildlife space, can minimize conflicts. Studies in urban ecology show that fostering coexistence with these predators ultimately strengthens biodiversity, enriches our city environments, and deepens residents' connection to nature.

Conclusion

As Oregon’s cities continue to grow, sustainable coexistence with urban wildlife is essential. Predators like coyotes, raccoons, and hawks are reminders of nature’s resilience and adaptability. By understanding and respecting these animals, we can create cities where people and wildlife thrive together, ensuring a vibrant and balanced ecosystem for generations to come.

Celebrating Bat Week: Oregon’s Bats and Their Vital Role in Our Ecosystem

Introduction

Bat Week, hosted by the National Park Service, is upon us! From October 24 to October 31, this annual celebration highlights the importance of bats and raises awareness about their contributions to ecosystems across the nation. Here at Callahan Wildlife, we’re excited to focus on the incredible bat populations of Oregon and explore the critical role they play in maintaining the health and balance of our environment.

Oregon is home to 15 bat species, each contributing to pest control, seed dispersal, and the overall vitality of our ecosystems. This Bat Week, let’s dive into why bats are such an important part of Oregon’s natural heritage and how you can help protect these fascinating creatures.

Oregon’s Bats: Nature’s Pest Control

One of the most significant contributions bats make to Oregon’s ecosystem is their role as natural pest controllers. A single bat can consume thousands of insects in just one night, making them invaluable to both farmers and city dwellers alike. In fact, Oregon’s agricultural sector greatly benefits from bats, as they help control pests that damage crops, such as moths, beetles, and flies.

Without bats, Oregon would see a dramatic rise in insect populations, leading to increased crop damage and the use of more chemical pesticides. Not only do bats help farmers save money, but they also reduce the need for harmful chemicals that can impact non-target species and degrade the environment. Their presence is particularly crucial in the summer months when insect populations peak, and bats work tirelessly to keep pests in check.

Pollinators and Seed Dispersers

While insect control is one of their most celebrated roles, bats also contribute to Oregon’s ecosystem as pollinators and seed dispersers. Though Oregon’s bat species don’t directly pollinate crops, they play a vital role in maintaining forest ecosystems by dispersing seeds. As bats fly from one roost to another, they unintentionally carry seeds that help regenerate forests, ensuring biodiversity remains intact.

Bats contribute to the health of Oregon’s forests, which are vital habitats for countless other wildlife species. By spreading seeds, bats help ensure that forests remain diverse, resilient, and capable of supporting other forms of wildlife, including birds, insects, and larger mammals.

The Threats Facing Oregon’s Bats

Despite their importance to Oregon’s ecosystem, bat populations are facing significant threats. One of the most pressing concerns is white-nose syndrome, a fungal disease that has already devastated bat populations across the United States. While this disease has not yet fully impacted Oregon’s bat species, the potential for it to spread westward remains a looming concern.

Additionally, habitat loss due to urban development and human disturbances threaten bat populations. As forests are cut down and old-growth trees, which serve as critical roosting sites, are lost, bats struggle to find suitable homes. Even wind turbines pose a risk to bats, as they can lead to fatal collisions.

The Economic Value of Bats in Oregon

While the ecological benefits of bats are clear, it’s important to also recognize the economic value they bring to Oregon. Bats save millions of dollars annually by reducing the need for chemical pest control in agriculture and forestry. Studies estimate that bats contribute billions of dollars in ecosystem services worldwide, and Oregon’s bat population is no exception.

For instance, by naturally controlling pests, bats help reduce the costs associated with agricultural damage and pesticide use. This benefit is passed down to consumers, as farmers are able to maintain healthy crops without raising prices due to pest damage. Bats also help keep Oregon’s forests healthy, which is essential for industries like timber, recreation, and tourism—key pillars of the state’s economy.

How You Can Help Oregon’s Bats During Bat Week

This Bat Week, you can take steps to protect and support Oregon’s bats:

Install a bat house: Bats need safe places to roost, and you can help by installing a bat house on your property. This gives bats a safe space away from predators and helps support their populations, especially in areas where natural roosting sites are disappearing.

Reduce pesticide use: By minimizing the use of pesticides in your garden or on your property, you help ensure that bats have plenty of insects to feed on. Avoiding harmful chemicals also benefits the entire ecosystem, creating a healthier environment for all wildlife.

Participate in local conservation efforts: Many organizations and wildlife groups in Oregon are dedicated to protecting bats and their habitats. Consider volunteering your time, donating, or even just spreading the word about bat conservation.

Stay informed: Educate yourself and others about white-nose syndrome and other threats to bat populations. The more we understand these issues, the better equipped we’ll be to take action and protect bats before it’s too late.

Conclusion: Oregon’s Bats Are Worth Celebrating

As we celebrate Bat Week with the National Park Service, let’s take a moment to appreciate the vital role bats play in Oregon’s ecosystems. From controlling insect populations to helping forests thrive, bats are an essential part of our natural environment. However, they face increasing challenges, and it’s up to us to ensure that these fascinating creatures continue to thrive in the wild.

This Bat Week, consider how you can make a difference—whether it’s through building a bat house, supporting conservation efforts, or simply spreading awareness about the importance of bats. Together, we can help secure a future where Oregon’s bats continue to soar through the night, keeping our ecosystems balanced and thriving.

Stay tuned to Callahan Wildlife for more insights into Oregon’s amazing wildlife and how you can play a role in conservation!

Green Infrastructure: How Cities Like Portland Are Designing for Wildlife

Introduction

As cities grow and evolve, so does the need for infrastructure that supports both urban life and the environment. One concept that’s gaining traction is green infrastructure. But what exactly is it, and why should we care? Why do cities need to invest in “green” infrastructure, and how does it relate to urban ecology? This post aims to answer those questions by diving into the world of green infrastructure, with a focus on Portland and other cities that are leading the way in sustainable urban planning.

Portland, Oregon, is often touted as one of the greenest cities in the U.S. The city embraces sustainability in its policies, initiatives, and community projects, many of which are tied to green infrastructure. Portland is our spotlight city for this blog post, but other urban areas like Seattle and Chicago are also making strides in designing for wildlife and reducing their environmental impact through similar strategies. But how much do these green projects cost, and what are Oregonians paying in taxes to support them?

What Is Green Infrastructure, and Why Is It Important?

Green infrastructure refers to a network of natural and semi-natural systems that work together to manage stormwater, reduce flooding, improve air and water quality, and enhance biodiversity. In urban settings, this infrastructure helps cities adapt to climate change, reduce pollution, and create healthier environments for people and wildlife. Essentially, green infrastructure turns the hard, impermeable surfaces of the city into vibrant ecosystems that benefit both nature and urban communities.

But what does this actually look like in practice?

Rain Gardens: Nature’s Filter

Rain gardens are among the most common green infrastructure features in Portland and other eco-conscious cities. These shallow, planted depressions allow stormwater runoff from hard surfaces like roofs, streets, and parking lots to be absorbed into the ground. Rain gardens act as natural filters, reducing pollutants before they enter waterways. They also slow down water flow, which helps prevent localized flooding, an issue that many cities face, particularly in areas with heavy rainfall.

In Portland, rain gardens are integrated into residential and commercial spaces, often along sidewalks or in parking lots. They not only address stormwater management but also provide essential habitats for local wildlife. Birds, butterflies, bees, and other pollinators are frequent visitors to these urban oases, benefiting from the native plants typically used in these gardens. The city encourages rain garden installations through various incentive programs, making them a common sight across Portland’s neighborhoods.

Roof Gardens: The Urban Habitat in the Sky

Roof gardens, or green roofs, are another critical component of green infrastructure. These gardens are installed on top of buildings and consist of layers that allow plants to grow in an otherwise inhospitable environment. Roof gardens help absorb rainwater, reduce the urban heat island effect, and improve insulation, which can lower energy costs for building owners.

Portland’s eco-roof program, launched in the early 2000s, has played a significant role in the proliferation of green roofs across the city. Green roofs provide a dual benefit: they manage stormwater runoff and create habitats for wildlife in areas where ground-level green space might be scarce. These rooftop ecosystems are particularly valuable for insects like bees and butterflies, offering food sources and resting places in the midst of the urban sprawl. As the city continues to grow, roof gardens represent a creative solution to environmental challenges while improving urban biodiversity.

Green Streets: A Sustainable Approach to Urban Drainage

One of Portland’s most innovative and widely recognized green infrastructure projects is its “green streets” initiative. Traditional streets channel rainwater directly into storm drains, which can lead to flooding and water pollution. Green streets, on the other hand, incorporate permeable surfaces, rain gardens, and bioswales—landscaped areas designed to slow and filter water before it enters the sewer system or groundwater.

Bioswales are particularly effective in filtering pollutants like oil, heavy metals, and debris from roadways. By allowing water to soak into the ground, green streets alleviate pressure on the city’s sewer systems during heavy rainfalls. Portland’s green streets initiative not only helps with flood control but also contributes to the overall health of the urban ecosystem. Plants and trees used in these projects provide habitats for birds and insects, while also improving air quality and reducing the urban heat island effect.

The Economics of Green Infrastructure: What Do These Initiatives Cost Oregonians?

While green infrastructure offers undeniable environmental benefits, it does come with a price tag. Cities like Portland rely on public funding to implement and maintain these projects, and that often means that local taxpayers foot part of the bill. So how much are Oregonians paying for these green initiatives?

Portland’s green infrastructure projects, including green streets, rain gardens, and eco-roofs, are largely funded through a combination of utility fees, public works budgets, and grants. For example, the City of Portland’s Bureau of Environmental Services (BES) is responsible for managing stormwater and investing in sustainable infrastructure. BES is funded through utility fees paid by city residents. In recent years, these fees have included surcharges specifically to fund green infrastructure.

On average, Portland residents pay around $70-$100 per month in utility bills, a portion of which goes toward funding these eco-friendly projects. While this might seem high, it's important to consider the long-term cost savings these projects can generate. Green infrastructure helps cities avoid costly infrastructure repairs by reducing flood risks, improving water quality, and extending the lifespan of sewer systems. In some cases, green infrastructure can even reduce energy costs for residents by cooling urban areas and improving building insulation.

State and federal grants also contribute to funding Portland’s green initiatives. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and other organizations often provide financial support for sustainable urban projects, easing the burden on local taxpayers.

Additionally, programs like Portland’s Clean River Rewards offer incentives for homeowners to install their own rain gardens or eco-roofs. These incentives can offset some of the upfront costs, making green infrastructure more accessible to residents.

Cost-Benefit Analysis: A Worthwhile Investment

While Oregonians do pay taxes and utility fees to support green infrastructure, the investment pays off in the long run. By preventing flooding and improving stormwater management, Portland saves millions in potential damage costs. According to a study by the American Society of Civil Engineers, every dollar invested in green infrastructure can save cities up to $6 in future infrastructure costs.

Moreover, the creation of green spaces boosts property values and enhances the quality of life for residents. A study by the Trust for Public Land found that properties near green spaces saw an average value increase of 5-15%. These economic benefits, combined with the ecological and social advantages of green infrastructure, make it a win-win for Portlanders.

Conclusion

Green infrastructure is more than a set of sustainable practices—it's a holistic approach to urban planning that benefits both people and wildlife. In cities like Portland, initiatives such as rain gardens, roof gardens, and green streets demonstrate how we can design urban spaces that are resilient to climate change while supporting the needs of local wildlife. While these projects come with upfront costs to taxpayers, the long-term economic, environmental, and social benefits make them a worthwhile investment. As more cities adopt green infrastructure, we can expect to see healthier, more sustainable urban environments that benefit all living things.

If you want to learn more about green infrastructure projects in Portland and other cities, stay tuned to Callahan Wildlife for future blog posts and updates on urban ecology!

October Book Review:

The Accidental Ecosystem: People and Wildlife in American Cities by Peter S. Alagona

Rating: 4/5 stars

Synopsis:

In The Accidental Ecosystem, Peter S. Alagona delves into the surprising transformation of American cities into thriving habitats for wildlife. As global wildlife populations decline, many urban areas now host an unexpected abundance of species, including large and charismatic animals. Alagona explores this paradox, showing that the resurgence of wildlife in cities is often an unintended result of human activity. Through engaging storytelling and rich historical context, he challenges readers to rethink urban landscapes and advocates for policies that support coexistence between humans and wildlife. The book promotes a vision of sustainable urban living that values biodiversity and harmonious human-wildlife interactions.

Accessibility:

This book is accessible and easy to understand, though it introduces a few complex topics. Alagona uses real-world examples of the challenges humans face with wildlife encroachment in cities, public spaces, and businesses. It’s science-based without overwhelming readers with excessive footnotes or jargon.

Who Should Read This?

I’d recommend The Accidental Ecosystem to those interested in urban ecology or learning more about wildlife in cities. While informative and engaging, this book is not for the general public unless they’re specifically interested in urban wildlife issues.

Rating Justification:

This book is well-written, with excellent sourcing and a blend of scientific and historical insights. However, due to its niche topic and focused audience, it didn’t leave an overwhelming impression, which is why I’m giving it 4 stars instead of 5.

Wildlife Road Crossings: A Solution to Preventing Collisions

Every year, drivers across the country hit between 1 to 2 million animals, according to the Federal Highway Administration. These incidents result in the deaths of hundreds of people, injuries to thousands more, and billions of dollars in damages (Holland, 2020). In Oregon, encountering wildlife on the road is a common occurrence, especially in rural areas. Imagine you're driving from Portland to Seaside on a foggy fall morning. Along the way, you might spot a fox, elk, or coyote crossing the road. Unfortunately, sometimes collisions happen, leading to totaled cars, injured drivers, and wildlife fatalities. But is there a solution to reduce these tragedies? Enter: Wildlife Road Crossings.

What are Wildlife Road Crossings?

Wildlife road crossings are specially designed infrastructure that allows animals to cross highways safely without stepping onto the road. These crossings come in two main types: overpasses (bridges above the road) and underpasses (tunnels beneath the road). Overpasses often feature fencing, guiding animals toward a safe crossing and away from the danger of traffic.

Why Are Wildlife Road Crossings Important?

In urban ecology, wildlife road crossings are becoming a vital tool to reduce collisions and protect both humans and animals. Animals need to move freely to forage, find mates, and access breeding grounds. Wildlife crossings not only help reduce vehicle-wildlife collisions but also allow animals to live their lives with minimal human interference. By giving wildlife safe passage, we can help preserve ecosystems and reduce the impact of human infrastructure on natural habitats.

Which Animals Use These Crossings?

Larger animals such as elk are quick to adopt these crossings, often using them earlier than other species (Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative, 2024). Bears and wolves, however, can be more cautious, taking up to five years to trust these structures. These crossings are also used by smaller mammals and even amphibians. In Oregon, the focus is primarily on large migratory animals like deer and elk, as these species are most at risk of road collisions.

What is the Cost of Wildlife Crossings?

Wildlife crossings are a significant investment. In Oregon, for example, the Oregon Department of Transportation has allocated $20 million for the Siskiyou Wildlife Crossing over I-5. The project will include both overpasses and underpasses at strategic locations to ensure the safe migration of species like elk and mule deer. Other successful projects, like the Lava Butte Wildlife Crossing ($18.9 million), have already proven the effectiveness of these crossings.

Conclusion: Look But Don’t Touch

As with national and state parks, the principle of "look but don’t touch" should apply when it comes to wildlife and roadways. Minimizing human interference in natural ecosystems is critical, and wildlife road crossings offer a proactive solution. By continuing to invest in these structures, we can protect both wildlife and drivers, reducing tragic collisions while preserving the natural movements of animals.

Welcome to callahan wildlife

Hello and welcome to Callahan Wildlife, where science meets community!

I’m thrilled to share my journey as an aspiring biologist and independent researcher. Here, you’ll find a blend of insightful blog posts, engaging discussions, and valuable resources centered around where wildlife meets humans. My aim is to create a space where the public community, researchers, and curious minds can come together to learn, share ideas, and explore the wonders of the biological world.

In addition to my blog, you’ll find links to my independent research, showcasing my ongoing literature reviews and studies for free. I believe that science is best shared, and I’m excited to connect with you as we explore the fascinating intersections of biology and the urban atmosphere.

Join me on this journey as we dive into topics that inspire curiosity and foster a sense of community. I encourage you to engage in discussions, share your thoughts, and help us build a vibrant network of science lovers.

Thank you for visiting, and I look forward to exploring this adventure with you!

Best,

Micah Callahan